Singularity

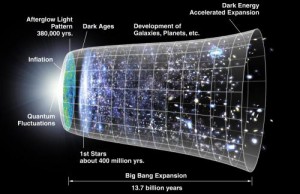

The other day, I got to thinking about singularities, as one does. Not the so-called technological or sociological singularity of Ray Kurzweil et al (which I think is just kind of silly), but the singularities that lie at the heart of the Big Bang and black holes. Mind you, the two singularities are not the same — the universe is not a black hole, and black holes are not little Big Bangs — but the basic concept, as I understand it, is essentially the same. A singularity is a construct of mathematics and physics and represents a region where we the laws of physics and mathematics simply break down. We simply can’t describe what happens at the heart of a singularity because our mathematics and our physics aren’t capable of doing so. There’s some philosophical debate as to whether the science has advanced sufficiently to a point where we can know what’s happening or we’ll never know because the mathematics will be forever beyond our ken. The point is, right we just don’t know what happens in a singularity, and we don’t even know if we ever will know.

So, it’s been established (more or less) that there are some questions we may simply never have the answers to. What happens inside a black hole? We don’t know. What happened in the first moment of the Big Bang? We don’t know. Can we determine both the precise location and velocity of a sub-atomic particle? No we can’t.

All this thinking about unanswerable questions made me dizzy while I was studying philosophy at UC Davis, and I loved it. And then I got to thinking about the limits of the human intellectual enterprise as a whole. Could it be that, in addition to questions we can’t answer, are there questions we can’t even ask?

Consider a housecat observing a human reading a book. To the human, reading a book means hallucinating vividly while staring at black marks on the remains of a dead, pulped-up tree. But what does it mean to the cat? Even the smartest of cats — such as our cat Rupert — wouldn’t know what to make of this. In fact, I would go so far as to suggest that the cat lacks the capacity to even ask what the human is doing. It doesn’t occur to the cat to question it, because the cat doesn’t understand the first thing about written communication, and the concept doesn’t even exist in the cat’s mind.

So what about the limits of human comprehension? Like the housecat, we’re obviously limited in what we can comprehend and understand. Do these limits mean that we can’t ask certain questions because we’ll never know where to look?

I once asked this question of one of my philosophy professors at UC Davis. Dr. A– simply replied, “What would be the point? Get back to your paper on Descartes.”

And, of course, I can’t provide any examples of questions that can’t be asked, because, by definition, if a question can be asked then it isn’t non-askable.

Finally, if a question is non-askable, does that mean there are vast swaths of knowledge that we simply can’t ever know? I didn’t study much epistemology in college, so I never really came across this question.

So to me, this little bit of questioning suggests a sort of singularity of human thought. Just as we’ll likely never know what happens inside the singularity of a black hole or what happened before the Big Bang, we may never know the limits of our own knowledge, simply because we can’t ask the relevant questions.

That’s all I got for now. My next blog post will be different, likely about our cat Rupert, the wicked smart cat, or Sherman, who attempts to escape our house every time the front door opens. But for now, this philosophical meandering is what you get.